On June 19, the U.S. State Department released its findings for the 2012 Trafficking in Persons Report. Released annually, the Trafficking in Persons report provides a comprehensive understanding on the state of human trafficking–both sex and exploitative labor–throughout the world.

Human trafficking is often referred to as 21st century slavery. Presently, an estimated 27 million people around the world are victims of human trafficking. But overall, there seems to be progress. As more people become aware of the issue, more is being done by governments, international organizations, grassroot organizations and individuals to combat human trafficking. Compared to last year, 29 countries, including Vietnam, were upgraded on the Trafficking in Persons report’s tiered list.

Vietnam was placed in the tier 2 group for this year’s report. Tier 2 countries are “countries whose governments do not fully comply with TVPA’s minimum standards but are making significant efforts to bring themselves into compliance with those standards.” Vietnam was on the tier 2 watch list (2WL) for 2010 and 2011. The watch list includes countries in danger of becoming greater trafficking zones.

According to the report’s country narrative for human trafficking in Vietnam, Vietnam is a “source and, to a lesser extent, a destination country for men, women, and children subject to sex trafficking and forced labor.” In regards to sex trafficking, the report notes that “Vietnam is a destination for child sex tourism with perpetrators reportedly coming from Japan, South Korean, China, Taiwan, the UK, Australia, Europe and the United States, although this problem is not believed to be widespread.”

Greater legislative action has been taken to protect victims and punish traffickers. A new comprehensive, anti-trafficking law was adopted in March of last year and came into effect January of this year. But enforcement still remains an issue: many NGOs charged that some local officials were complicit in trafficking, especially those working near border crossings and checkpoints. Additionally, the growing prevalence of brokered marriages has increased trafficking risks in Vietnam:

Some Vietnamese women moving to China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Macau, and increasingly to South Korea as part of internationally brokered marriages are subsequently subjected to conditions of forced labor (including as domestic servants), forced prostitution, or both. There are reports of trafficking of Vietnamese, particularly women and girls, from rural provinces to urban areas, including Hanoi, Ho Chi Minh City, and newly developed urban zones, such as Binh Duong. While some individuals migrate willing, they may subsequently be sold into forced labor or commercial exploitation.

Labor exploitation is an equally pressing concern and may indeed be more widespread. Labor exploitation operates at both the highly-coordinated trafficking ring level and through thuggish coercion. On the one hand, children are being “subjected to forced street hawking, forced begging, or forced labor in restaurants in the major urban centers of Vietnam, although some sources report the problem is less severe than in past years.” But there have also been incidents where Vietnamese and Chinese organized crime groups entrapped Vietnamese children into forced labor on cannabis farms in the UK: victims were flown to Russia with an agent, then transported by truck to Ukraine, Poland, the Czech Republic, Germany and France before arriving in the UK.

The lure of working overseas is also contributing to human trafficking risks in Vietnam. There are many labor-exportation companies, some state-affiliated, that send workers to Thailand, Malaysia, South Korea, Laos, the UAE, Japan, China, Taiwan, Cambodia, Indonesia, the UK, the Czech Republic, Cyprus, Sweden, Trinidad and Tobago, Costa Rica, Russia, Libya, Saudi Arabia, Jordan and parts of the Middle East and North Africa to work in fishing, agriculture, mining, logging, manufacturing and other labor-intensive industries. Some of these companies reportedly charge up to $4250 in fees to send a worker abroad–roughly 3 times the current per capita income in Vietnam. Because of the high cost of securing a job overseas, many of these workers become trapped in debt bondage. A 2010 study of 1265 migrant workers from northern Vietnam found that nearly half of the workers had become trapped in debt bondage after going overseas. After arriving in their destination country, many victims also subjected to harsh working conditions and abuse.

Human trafficking in Vietnam and elsewhere in the world is a truly complex problem, and solving it isn’t as simple as rounding up the bad guys and putting them in jail. Its deeply intertwined with social, economic, political, cultural and moral issues. While VNHELP doesn’t manage programs that directly address human trafficking, we do our best to open the doors of opportunities to children, women and men through education, vocational training and institutional support to lower their vulnerability to trafficking. We believe we are tackling some of the root causes of trafficking. We encourage you to continue reading on the issue and you can contact us if you’d like references to more information on the matter. As a starting point, our staff recommends the book Half the Sky: Turning Oppression into Oppurtunity for Women Worldwide by Nicholas Kristof and Sheryl WuDunn, but please be reminded that trafficking affects both women and men.

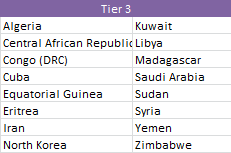

Note: Somalia is filed under “special case.”